Memories of Ron Cheetham

I was born on the 10th February 1933 in number 35 Long Row in the little mining village of Coxhoe in County Durham. At the tender age of 4 years old, I started school in Coxhoe Infants in the Front Street.

I was the eldest child, then our Harry, Gordon and little sister Violet. We slept four in a bed, what we called top’n’tail, that meant; two with their heads to the headboard, and two with their heads at the bottom. It was so cold in the winters that Mam used to wrap a hot iron oven-shelf in an old sheet and put it in the middle of our bed to keep us warm. Dad would also throw a clippie-mat on top for luck. The inside of the sash windows used to freeze over and we used to break the ice from the window ledge.

Our house was infested with black beetles which we called ‘blackclocks’. They were as big as ponies and able to put a saddle on them. Legend has it that we were so poor that we couldn’t afford to decorate the walls and, armed with a shoe in one hand, we would switch on the lights in the morning. The blackclocks would scurry up the walls and we would splat them them all over the wallpaper. We made some lovely patterns.

Blackclocks seemed to play a memorable part in my childhood. They were everywhere and mainly came out at night to scavenge for food. We never left our shoes or clothes on the floor and we always gave them a good shake before putting them on in the morning. Dad tried poisoning them, burning them and even trapping them but to no avail. If we got rid of them, they would simply move next door. And so, the process went on right to the top of the street until it came back to our turn again to be invaded.

From Coxhoe Infants I went to Cornforth Lane School. Mr Potts was the head teacher. Mr Trew taught woodwork. I loved woodwork.Eric Barber was one of my greatest friends at school. We used to play ‘horse-fights’. Eric was a very tall boy for his age and therefore was always the horse. Coming home from school we would play marbles in the roadside gutters. Our knuckles and knees were always ‘set in’ with muck. I still have a big jar of marbles. Sometimes we would come across a nice juicy bit of pitch that had squeezed into the gutter. We would hack it up and then divide it among us and chew it. It was great stuff was pitch – like a mixture of Marmite and candle wax – it was lovely.

There were no buses to take us to school in those days. We had to walk from Long Row to Cornforth Lane. But we knew better in every sense of the word.

In the summer, the womenfolk used to get their ‘poss-tubs’ and ‘poss-sticks’ out in the back lane. The poss-tubs were filled with hot water and Acdo and Dollytint. The mucky clothes were thrown into the poss-tubs and the women would pound hell out of them with their big, heavy poss-sticks. All the women would gossip away whilst their big muscley arms rippled under the strain. The pounding and squelching went on for ages in perfect synchronised rhythm. Stories used to be passed up the ranks and when they got to the end of the street they were completely different stories.

One day, I remember leaning over the top of the poss-tubs and I fell in head first. I splashed about like an idiot until I was hoisted out by the scruff of my neck. I certainly had a good bath that day – and a good hiding. This I didn’t mind too much. It was the poss-stick that gave me the headaches.

Some of the littler kids used to be put in the poss-tub after the washing was done – like, sort of open-air baths. They used to come out white as ghosts with the thick scum around their necks like the Acdo ring of confidence.

One Sunday, I heard the Church Lads Brigade outside. I ran through the house and crashed straight into my mam. She was carrying a big pan of boiling water at the time. I got the whole panful down my right arm. Instead of putting cold water on my scalded arm, the district nurse applied ‘Bluestone’ which made it worse. I used to hide under next-door’s kitchen table when I knew that Mrs Ward was coming. After a few months, I got pneumonia and had to be taken to Durham County Hospital. Two skin-grafts were taken from my leg over a period of one year. I still have the scars today.

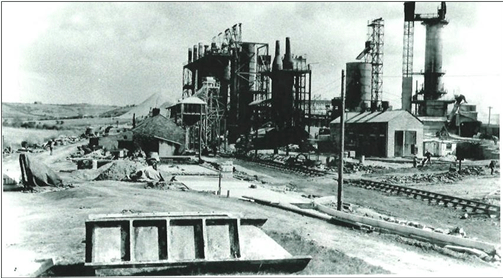

My dad worked at Basics. My mam used to make him a couple of sandwiches, usually the fillings were either condensed milk or sugar. Rarely he would get jam – better known as ‘Pitman’s Ham’. She also made some tea in a long can with a wire handle over the top. That handle used to cut into my hands by the timei got to where I was going. “here yer are then our Ronnie! Gan and take yer dad his bait!” she’d say.

So, off I’d trot as proud as punch, can in one hand and bait under my arm – stopping once in a while to swap them over. The kilns were stifling hot. There would be a man waiting by the lift – “Hello Son!” he’d say. “Yer dad’s at the top. Jump in the cage and I’ll tak’ yer up!”.

At the age of nine, I felt like a real man going up in that lift. I could smell the lime and coke from the process plant. Dad would always be waiting for me. “come on son!” he’d say, “come and I’ll show yer around”. I couldn’t imagine scenes like that today.

War came and life was great for me. We were blind to the true horrors of it all. Something interesting was always about to happen. Us lads named ourselves ‘The Long Row Gang’. We would often go around to Coxhoe Hall prisoner- of- war camp. The massive house was once the residence of Elizabeth Barrett Browning – the famous author. We liked the German prisoners the best and we would visit them for a chat. No-one ever stopped us. We would sit with them in their huts and they’d often give us buttons and sometimes even a badge or two.

Sweets, food and clothing were rationed. To get sweets, we had to stand in long queues at Panico’s (now Laings). There was the Canteen, now the bike shop, for 6d (2½p) we received a can of hot soup.

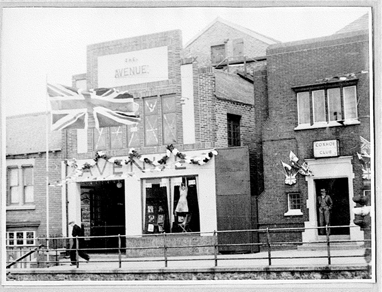

The cinemas were the Gem – now the café, and the Avenue. It was 3d (1½p) to sit on the form right at the front. The cinemas were always packed and we had to be sure to be at the front of the queue to be able to get on the form. Films shown were often ‘Hop-along Cassidy’ and ‘Roy Rogers’, ‘Tom Mix’ – they were always the ‘goodies’. The comedy ones were usually ‘Abbott and Costello’, Laurel and Hardy’ and ‘The Three Stooges’. The Avenue was the posh cinema. The queues would stretch right back to the police station – now the dental surgery. To go upstairs in the balcony seats would cost 1s-0d (5p). Up in the balcony I felt like God.

My dad and mam bought me my first bike – a Hercules. Because I was the only one with a bike in my school I did all the messages for the teacher.

Our family moved to number 15 Park Avenue and I left school one Friday at the tender age of fourteen. I started work the following Monday at Colonel Dodd’s farm. I don’t recall whatever happened to Colonel Dodds because the farm was run by his wife and daughter. They were helped by a farm ‘hind’ who was a great guy but I can’t remember his name.

At the age of fourteen I wasn’t the height of a ’pennyworth of copper’. The hind would take me to the stables. Inside, there were two massive draught horses –Clydesdales. To me, they were as big as elephants. “First the Braffen!” he said. I could just to say lift that thing. I had to stand on a box just to get near to the horse’s head. The hind laughed until the tears ran down his face.

The next few months were really hard work for me. Winnie, the daughter, made sure she got her money’s worth out of me. There was no tractor on the farm and to sow the corn we had to what they called ‘fiddling’. It meant that I had to fill a sack with corn, hoist it up onto my shoulder and let it run out into a trough. The corn-seed was then scattered side to side, as if playing a fiddle, up and down the fields.

I left the farm after 1+ months in 1946. I started work for East Durham Co-op Dairies, delivering milk to West Cornforth and Chilton.

Leaving the Co-op at the age of seventeen in 1946, I started working at Thrislington Colliery at West Cornforth. My first job down the pit was to separate the stones from the coal. After three weeks I was transferred to the ‘tipplers’. I was on that job for a year and given the job of moving tubs into the cage. The cage was a huge lift that would carry miners, coal-hubs and even pit-ponies down the shaft and into the bowels of the earth. One mistake could have meant going down the shaft without the aid of the cage.

At the age of twenty, I transferred to Dean and Chapter mine in Ferryhill. I spent six months training for my new job underground.

West Cornforth pit -better known as ‘Doggy’ because everyone in the colliery seemed to have a dog – didn’t have any pithead baths. The lowest seam was only a half metre high x 40 metres long each side of the main gate. It was a bottom-belt conveyor. We miners worked in the middle of the seam and had to crawl 20 metres whilst carrying a pick, shovel and cap-lamp. We had to make sure that the Davy lamp didn’t go out or it meant total blackness. For this we received 1s-0d (5p) per day. Bait was usually jam and bread and water. I tried carrying a flask a few times but they always ended up broken.

Miners finishing their shift came up as black as crows. To get home we had to catch the Blenky bus (Scarlet Band). We were still in our pit clothes with our water bottle hung on our belts and wearing our pit helmets. No-one even gave us a second glance.

My brother, Harry, started Doggy pit before me. We managed to get onto the same shift because I had my bike. Harry used to sit on the seat whilst I peddled (because I was the daftest!).

The first job was underground on what we called ‘Developments’. This involved power-driving through solid rock faces approximately 2 metres square. We then had to shovel the loose rock into tubs and hitch a pony to the tub. The filled tubs were hauled to the main gate otherwise known as the ‘exit gate’ in other pits but were 4 metres square. We would continue driving through the rock until we reached a coal seam.

The next job was ‘pulling and drawing’ which meant pulling the conveyor belt forward to the next level. This was for the coal face workers on the next day or shift. These workers (hewers) lay on their sides in the low seams and hacked out the coal with picks.They were covered with black scars where the coal dust had got into their wounds that healed over and looked just like indefinable tattoos.

As the seam advanced, we had to draw out the old shoring timbers and hoped that the roof would collapse. This took the pressure from the coal face. Other jobs comprised of drilling the coal face at 2 metre centres. This was to assist the shot-firers, who would pack the bored holes with explosives and blast the coal seam. The loosened coal was then shovelled onto the conveyor belt for hauling out from the pit. Thrislington and Greyhounds were joined up underground. The coal from the Greyhound drift came to Thrislington by Main and Tail Transport.

Grandad, Dick Cheetham, lived in Heugh Hall. I used to go with him to the ‘Pit Laddie’ pub which is now under the A1M motorway. I would listen to the old miners’ telling their tales of days gone by, never to return.

Granddad and Grandmam Lindoe lived in Reading Room Street, Quarrington Hill. They had a gramophone player. I loved to listen to the old records. Grandmam couldn’t walk and used to just lie in bed smoking her old clay pipe. She had an old Aspidestra plant in the corner of the bedroom.

The seams of coal at the Greyhounds were good seams of 1 metre x 2 metres. I injured my eye working there and had to spend 4 weeks in Sunderland Eye Infirmary.

Coxhoe Drift was very wet. That’s where I had to learn to use the coal-cutting machines. The seam of coal I worked in was called The Harvey 3 foot.

I bought my first motorbike, a 250cc BSA. I passed my test on my next bike, which was a 350cc BSA. My friend Charlie Sargason and I would ride that bike over the moors to Kirby Stephen and then go on to Blackpool. I was a real ‘bird-puller’ was that bike. I graduated to a 650cc Gold Flash. I had a few problems with that bike so I sold it to buy a 500cc Shooting Star. It was my best bike – bar none.

One of my greatest hobbies was going to the ice-rink in Durham. That was where I met my future wife Ann. I learned later that she had pointed me out from the rest of the crowd and said “I’m going to marry him one day!”. Little did I know at the time that my future was planned for me.

I married Ann Crawford on the 18th of October 1958. Our daughter Sharon was born 17th of August 1961. Our son Peter was born on the 14th of October 1965.

I passed my test for a PSV licence in 1965 and did part-time driving for Colin Heads buses. I also left the pit in 1965 to work for Gatenby’s Carpet shop in Coxhoe. My jobs varied from fitting carpets to erecting TV aerials.

Thrislington pit closed in 1967 and tolled the death knell of deep-seam coal mining as we know it. We complain of the cost of gas and oil today – but what was the real price of coal – in human sacrifice.

Many were the tears of frustration shed on our journeys down to the Pit. But, many too were the laughs we had along the way. And perhaps, just perhaps, someone may find time to read my little book and reflect on those so-called ‘Good-old-days’, the poverty, the filth and pollution, the hacking cough of the Black Lung, the friendship and dedication of the miners – And Smile.

A friend once said to me; “You need to have known the misery of poverty before you can appreciate the Joy of Giving”.

Ronnie who lived at 1, Browning Hill, was helped by his friend and neighbour Ray Watson who lived “out the back” to write these memories. Ray was a prodigious author. Sadly since these memories were compiled both Ronnie and Ray have passed away.

We will always be grateful that they took the time to recount times gone by.