(Copyright Coxhoe Local History Group)

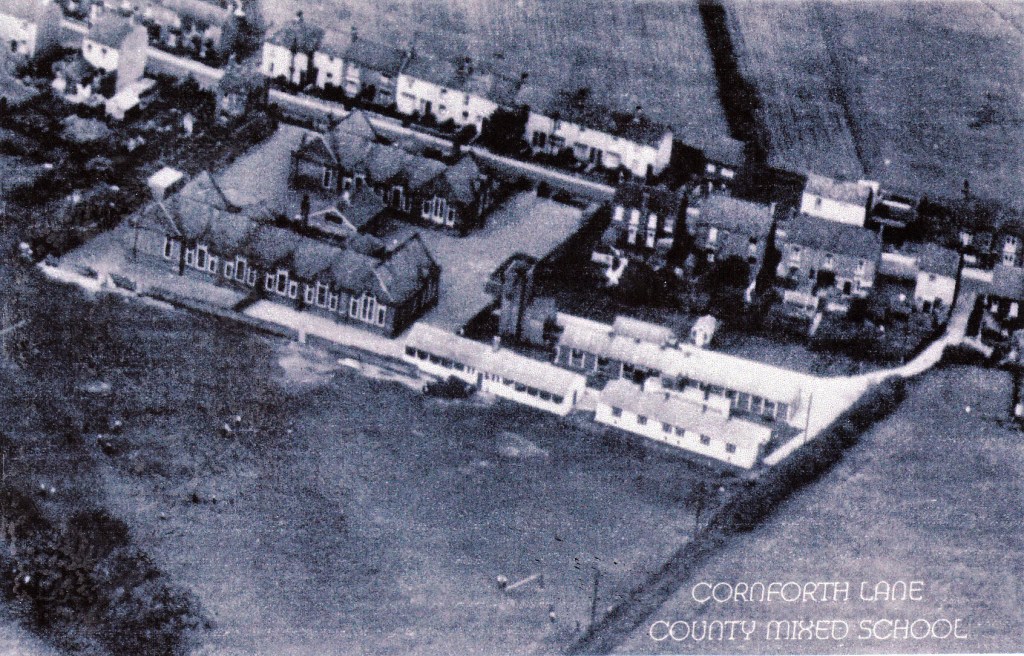

Cornforth Lane School in the 1930’s

Cornforth Lane School, Coxhoe in the 1930s

I was born at 31, Co-operative Terrace, Coxhoe in 1928 and entered Cornforth Lane Council School in September 1933. This is the same substantial building which is used today by Coxhoe Primary School. In those days there were no Primary or Secondary schools. In every village there was a ‘through’ school catering for children from 5 to 14 years of age (the statutory starting and leaving ages of pre-war schooling.)

Cornforth Lane School was always in the vanguard of educational ideas chiefly because of its good examination results at 11 plus and after. It was chosen to host the ‘Higher Tops’ which were special forms devised for children who had missed out on entry to the grammar school. They followed a parallel syllabus with French and all mathematical disciplines such as Geometry, Algebra, and Trigonometry as well as the basic subjects. The pupils were then entered for ‘occasional’ places at the Grammar Schools at the ages of 12 and even13. I remember children coming from all surrounding schools even as far away as Deaf Hill and Trimdon to join these classes, and most were successful – hence the good reputation of Cornforth Lane School.

However it was not only the Senior end of the school which was famous. In 1933 when I entered the ‘babies’ class the Government had just issued a Report on Education laying down its aims and hopes for the future.

As this was a period of severe economic depression and great deprivation there was great concern for the Health and Welfare of school children and particularly the youngest. It was an age when educational pioneers were working to establish pre-school education so that children who lived in overcrowded and poverty-stricken homes could be given a better start in life.

When I compare pictures of the past, Coxhoe never seemed to be as bad as some places in the North East. Of course there were some houses with outside earth closets and one cold tap (usually in the pantry),but this was a prelude to one of the greatest government building programmes of social housing (council houses) of the 20th century.

In Coxhoe the largest estate was to be ‘The Grove’. I don’t ever remember children running round in bare feet as was common in the larger towns such as Sunderland or Gateshead. However there were children who wore wellingtons in the summer and sandshoes in the winter – obviously hand-me-downs. Charitable institutions came into schools to assess those in the greatest need. I remember the Police coming into school to look at our footwear. As we all sat in iron-framed dual desks we had to swing round so that our feet were in the aisles whilst the assessors (policemen) looked at our footwear. Sometimes they asked a child if they could see the soles of their shoes. Try as I did and much to my disappointment I never qualified for replacements. However there was no obvious ‘charity’. I never saw new shoes handed over, nor was any one singled out because they had received ‘charity’.

My first class teacher was Miss Price. She was young, pretty and dedicated. Our large classroom had the traditional desks in rows at one side and right on target with current educational thinking, the other half of the classroom had a rocking horse, swing boat, slide, easels, clay, sand and water. It was a great start to full-time education. Unfortunately there were limitations for carrying out all the government initiatives. There were no school meals. Everyone went home at lunch time and came back for half past one.

As the only car owners were the Vicar, the Doctors and the Woods (of Coxhoe Hall, every body walked to school and back.

However we did get school milk which was free for some children and others had to pay a ha’penny (half penny) a day for one third of a pint of milk.

This was delivered from the Co-operative Dairies at Wellfield (Wingate) in small, returnable glass bottles with a card inset lid. In the cardboard lid was a perforated hole which, when punctured took your straw. (These were the days before plastic) The milk monitors brought the milk in crates to the classrooms and sometimes in winter if the milk was frozen we had to put it on the radiators to thaw. I longed to be a milk monitor but that job was usually for the boys.

The toilets were ‘across the yard’ and being unsupervised left a lot to be desired. I remember one master-system flushed all the toilets at once and this was operated by the caretaker. Meanwhile constant use meant that the toilets were usually in a revolting condition by the time the mass ‘flush’ took place. It was said that some children made themselves ill because they refused to use the school toilets and waited until they got home.

Miss Price was a dedicated teacher. I don’t remember anyone who could not read within about one term – all were taught formally by phonic methods.

My second teacher in what was called Standard 1, was Miss Parker who (unfortunately for me) had been in my Mam’s class at Spennymoor School and who relayed any misdemeanours back home. When I wrote in my composition on ‘My Mother’ (yes- composition at six and a half) – ‘My mother is little and fat’ she told on me!!

My final infant class was Standard 2 with Miss Beaton as teacher. She was also the teaching Head of the Infants School. She travelled from Chester-le-Street by bus and walked from the bus stop ‘along the lane’ to the school. She moved during the war to be Head of Dean Bank Infants – a much bigger school.

The Infant building was the front building and the Junior and Senior school occupied the building behind with a different head teacher. Miss Hannah Beaton was a force to be reckoned with, but as I was a ‘trusty’ she made me a class monitor. This meant giving out the pencils and exercise books – maybe because I could read all the names on them.

Another of my duties was to go to the teachers’ staff room about a quarter of an hour before playtimes to put the kettle on the coal fire for the teachers’ tea – nobody had electric kettles in those days. The kettle was black cast iron and the fire had to be poked level to put the kettle on the glowing coals – a very important job, but what price health and safety???

Miss Beaton was also very forward thinking in that she introduced glove puppets into our English curriculum. We became so good that we performed at garden parties and at the Child Welfare centre which functioned in the Primitive Methodist school room – now Gatenby’s carpet shop. One of my cousins had speech problems (stammering) and the puppet show was a great confidence builder for him!! So Special Needs were also an important consideration even then.

However I fell from grace with Miss Beaton, when I cut out a Christmas tree the wrong way round. Everyone who got it wrong was hauled out to the front of the class for the strap (made of leather) and when it came to my turn, I said I would tell my dad if she hit me. Wow!! Father was sent for to apologise for this very rude child who had questioned the teacher’s authority and he had to promise that it would never happen again. Certainly this was a dent in my happy school days.

Added to this we also used to do country dancing and give displays. In the final July of my Infant days (actually 24th) we were giving a display in the school yard for our parents and I remember the dances were ‘Haste to the Wedding’, ‘Rufty Tufty’ and ‘The Butterfly’. I looked round for my mam but could only see my auntie. I was bitterly disappointed but when I got home I found I had a new baby sister (our Doris) – no advanced preparation/counselling for new additions to the family in those days!

Before the outbreak of war both Miss Parker and Miss Price had left to get married and in those days married women were not allowed to continue teaching. Incidentally this changed when war broke out and the men teachers were called up – the women then had to ‘man the pumps’.

By the end of that school year, 1935, I had experienced a few knocks and was quite glad to be going into the next department. Summer holidays were usually four weeks – the whole of August.

A great treat on the way to school was to call at some of the small shops for sweets. I remember we passed Hope’s, Sinclair’s, Swinbank’s and Dawson’s. The latter were in School Avenue and were my favourite, because you could buy sherbert dib-dabs for a ha’penny. This was allowed on Friday night on the way home from school.(they were messy!)

The next department was the building farthest away from the road. At one end were the Junior Classes and at the other end were the Seniors and Higher Tops. The Head of the Junior and Senior School was Mr. Smith. He lived in Vicarage Terrace and was known to everyone in Coxhoe as ‘Boss’ Smith.

Between the two schools there was a detached block which was the Woodwork department under Mr Trewick (of Coxhoe). The senior girls had Cookery with Miss Summerbell who lived at Slake Terrace, West Cornforth.

The Cookery department was part of the Infants building, although quite separate. There was also a flourishing school garden and some of the senior boys did gardening and the produce was sold to parents. The boys’ and girls’ playgrounds were separate. On wet days we were not allowed into the main school building and had to stand, huddled together in the cycle sheds, which were near the boundary walls of the school.

As there were children coming from outlying farms and other villages, packed lunches were allowed and a teacher on duty supervised an urn of hot water to provide cocoa.(Nescafe, Bournvita, Hot Chocolate had not yet been invented, and certainly there were no cans or individual bottles!))

I held the Headteacher in great awe. I remember him flogging the big boys for very mild misdemeanours(such as pinching apples), but I kept out of his way and got my head down. I was only in two classes before the eleven plus, Standard 4 and Standard 5.

The first teacher was Miss Amy Parkin, from Spennymoor. She was small and dynamic and we had to work very hard. Even though she was quite sarcastic with the strugglers, I got on alright with her and although there was a lot of rote learning of tables, poems, psalms, and passages of scripture I have never forgotten some of the things I learned with her.

I remember the introduction to pen and ink and two boys being chosen as ink monitors who had to collect the individual ink wells into a tray which had holes for each ink well. There were usually two ink wells at each dual desk and sometimes people stuffed them with blotting paper. This gunge had to be removed and the ink wells washed out every Friday afternoon.

Schools did not rise to real ink. Ink powder was mixed with water by the ink monitors in an ink kettle which had a spout like a ‘mini’ watering can. There were often spills and people who got ‘blots’ on their work usually got the stick! A damaged (crossed) pen nib could wreak havoc on any written presentations. Hard times!!

Next I went into Miss Nellie Jamieson’s class, Standard 5. This was the eleven plus class. Miss Jamieson lived in Coxhoe where her father was a watch maker and repairer. His workshop was in the premises now occupied by the Bank Café.

She must have been in her forties and therefore very experienced. We seemed to be always writing essays and doing intelligence tests which were preparation for the eleven plus. However she had a wonderful library in her classroom and it was at this time I read most of Dickens, Sir Walter Scott and many other classics. Since then I seem to have only read for exam purposes, because I have always had to be reading something else for information.

When it came to the end of the year (1938) they did not know what to do with me as I was three weeks too young to take the 11 plus, so I was put into the Higher Tops. Post-11 education at Cornforth Lane therefore had two streams and was very challenging. For the first time I met male teachers. We did Maths with Mr.(Teddy) Elves from Tudhoe, and French with Miss Wilson from Spennymoor. Also in the Senior Department was Mr Thompson who travelled to Coxhoe on the ABC bus from Darlington. He seemed quite elderly. He was a great pianist, taught music and played for the school assemblies. Also in the department were Miss Flora Parkin (cousin of Miss Amy) and Miss Nichol from Spennymoor. One of these teachers finally bought a car and brought the others to school.

However the ‘heart throbs’ of the upper school were Mr. Riley, Mr. Soulsby, Mr. Russell and Mr Boyne, who within a few months of war being declared were in the forces. Mr Charles Riley (Chuck) was a pilot in the RAF who never returned, and Mr Soulsby joined the army and returned to marry Miss Summerbell, the cookery teacher, at the end of the War. Ahh!

So to the declaration of war and the arrival of evacuees.

In 1939 I was in my last year at Cornforth Lane. In late September we were told not to report for school because it was being used as a Reception Centre. I must say I was ‘miffed’ to say the least that these ‘usurpers’ were taking over our school and we were shut out. I remember going down to the school and looking through the iron railings (before they were cut down for the ‘war effort’).

The evacuee children arrived from Sunderland looking very forlorn. They carried a bag or small case with their clothes and the ubiquitous gas mask in a box. The large scale anticipated bombings at the ports did not take place and the children eventually drifted back to their homes. Those billeted round us were back home by Christmas but some stayed longer.

Air raid shelters were built in the school yard between the two schools and we practised air raid drills and sucking barley sugar in the shelters. I never felt insecure and life continued in its old pattern thanks to the devotion and care we received from the staff of Cornforth Lane School and the support of our parents. The 1930s had been a tough time, but everyone pulled together and I am glad that I lived in such a vibrant historic period.